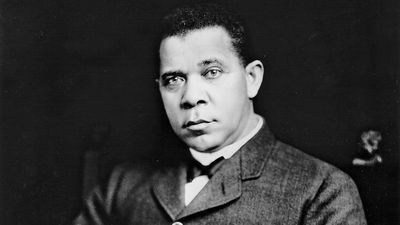

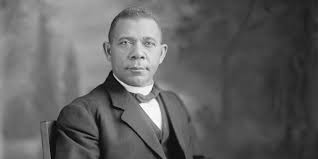

Welcome to the “Black History Month” edition of the Evolving Folks Project’s Evolved Man of the Week profiles. Each week in February, we will highlight a historical Black male figure who embodies what it means to be an evolved person, famous and non-famous people alike. The world needs to know their stories and deeds. This week’s honor goes to the American educator, author, and the most influential African American leader of his time, Booker T. Washington.

Booker Taliaferro Washington was born on April 5, 1856, in a hut in Franklin County, Virginia. His mother was a slave who worked as a cook for the Burroughs family, the plantation owners. Washington did not know his father, who was white. At the conclusion of the Civil War, James and Elizabeth Burroughs freed all enslaved people they owned, including a 9-year-old Booker, his siblings, and his mother, Jane. Washington’s mother established her family’s new residence in Malden, West Virginia. Shortly after, she married Washington Ferguson, a Black free man. Upon the conclusion of the Civil War, Washington Ferguson’s family moved to West Virginia, too. As a young boy, Booker T. found employment in salt furnaces and coal mines there. Despite these challenges, he was determined to pursue his education. In 1872, he walked nearly 500 miles to enroll at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, working as a janitor to pay for his education.

Tuskegee, Alabama, appointed Washington to lead a new school for African Americans in 1881, marking a significant career change for him. With minimal financial resources and operating in temporary quarters, the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute began its operations. For over three decades, under Washington’s guidance, students actively took part in building their school. They constructed facilities, cultivated crops, and gained vocational skills. By the time he passed away, Tuskegee had expanded to encompass over 100 buildings and nearly 1,500 students. Today, Tuskegee University is a prominent historically Black college in Alabama. At the time of Washington’s death, Tuskegee Institute, which had started with an appropriation of just $2000 from the Alabama state legislature, had a faculty of 200, an enrollment of 2000, and an endowment of $2 million.

In Washington’s view, the priority for African Americans post-Reconstruction was to build economic strength via education and industrial skills, rather than immediate confrontation with Jim Crow segregation.

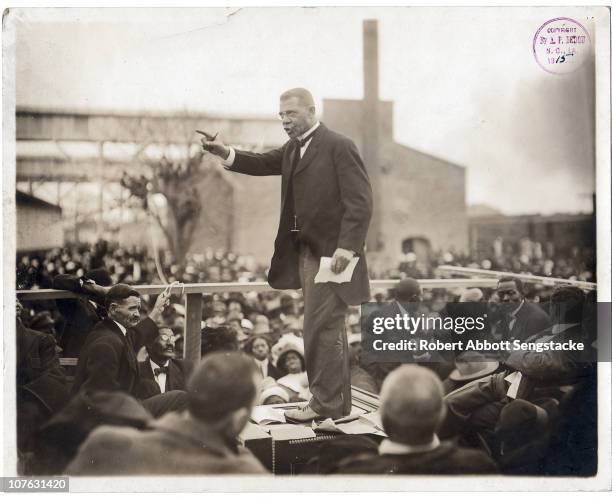

He outlined this philosophy in his famous Atlanta speech on September 18, 1895:

“In all things that are purely social, we can be separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

The approach, which his detractors termed the “Atlanta Compromise,” achieved widespread approval from white politicians and the Black community alike, but simultaneously attracted severe criticism. W.E.B. Du Bois presented a significant challenge to Washington’s leadership by advocating for full civil rights and a formal academic education rather than solely vocational training. In 1909, Du Bois and others established the NAACP, largely in response to Washington’s policy of accommodation.

W.E.B. Du Bois vehemently opposed his speech, denouncing what he termed “The Atlanta Compromise” in his renowned 1903 book, “The Souls of Black Folk.” The Niagara Movement (1905-1909) was formed in response to Washington’s racial views.

The Black community’s strong regard for Washington meant that dissenting viewpoints were effectively silenced. Washington’s harsh criticisms of Black media and Black intellectuals of his day, who questioned his ideas and leadership, were criticized by Du Bois and others. However, current scholarly analysis provides a nuanced perspective on Booker T. Washington’s political thought. While outwardly supporting segregation, he secretly provided financial backing for lawsuits that contested it.

President Theodore Roosevelt extended an invitation to him in 1901, making him the first African American to dine at the White House, and he later served as an advisor to both Roosevelt and President Taft. Among his many books, his autobiography Up from Slavery (1901) is renowned and remains a vital read.

Washington died in 1915 from congestive heart failure at age 59. While his views fell out of favor during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, later historians have offered more nuanced perspectives on his pragmatic approach, given the severe limitations of many people in Booker T.’s era. Today, we honor Booker T. Washington as our Evolved Man of the Week.